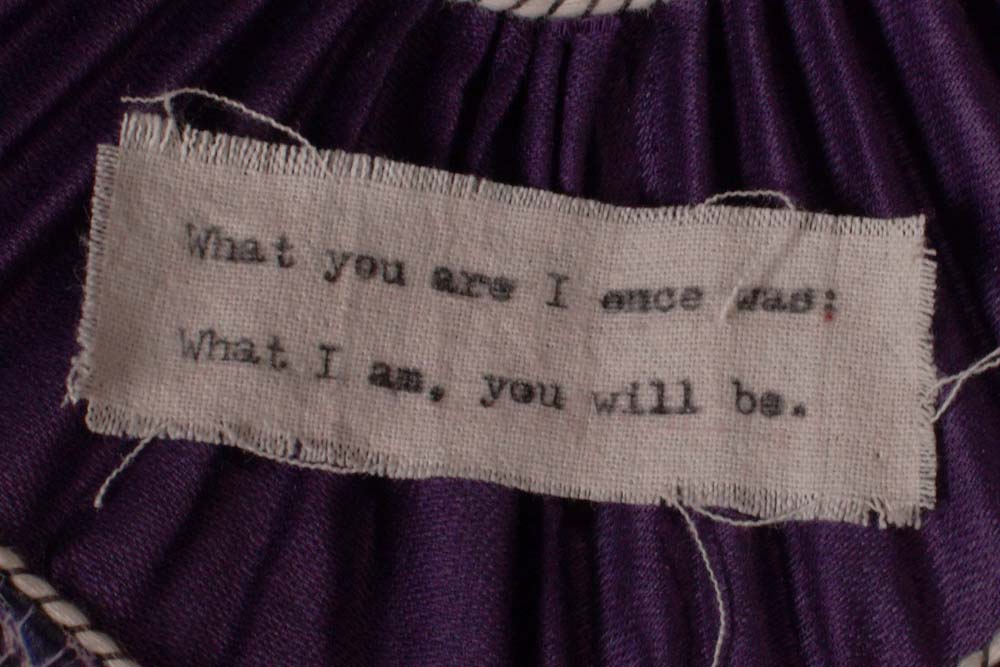

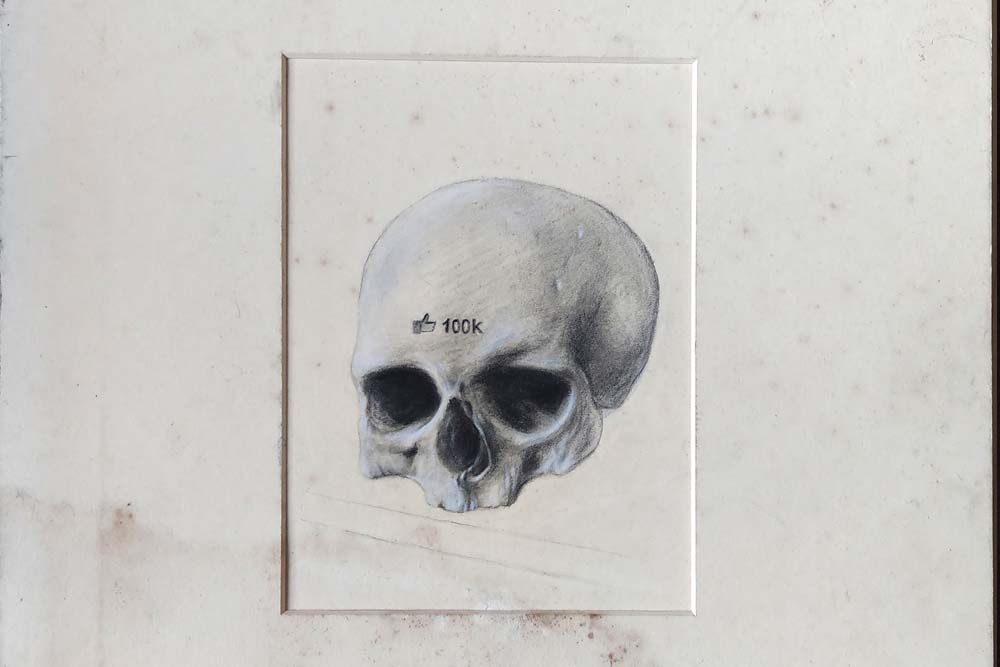

“Hodie Mihi. Cras Tibi.”

("Today me. Tomorrow you.")

An ossuary inscription

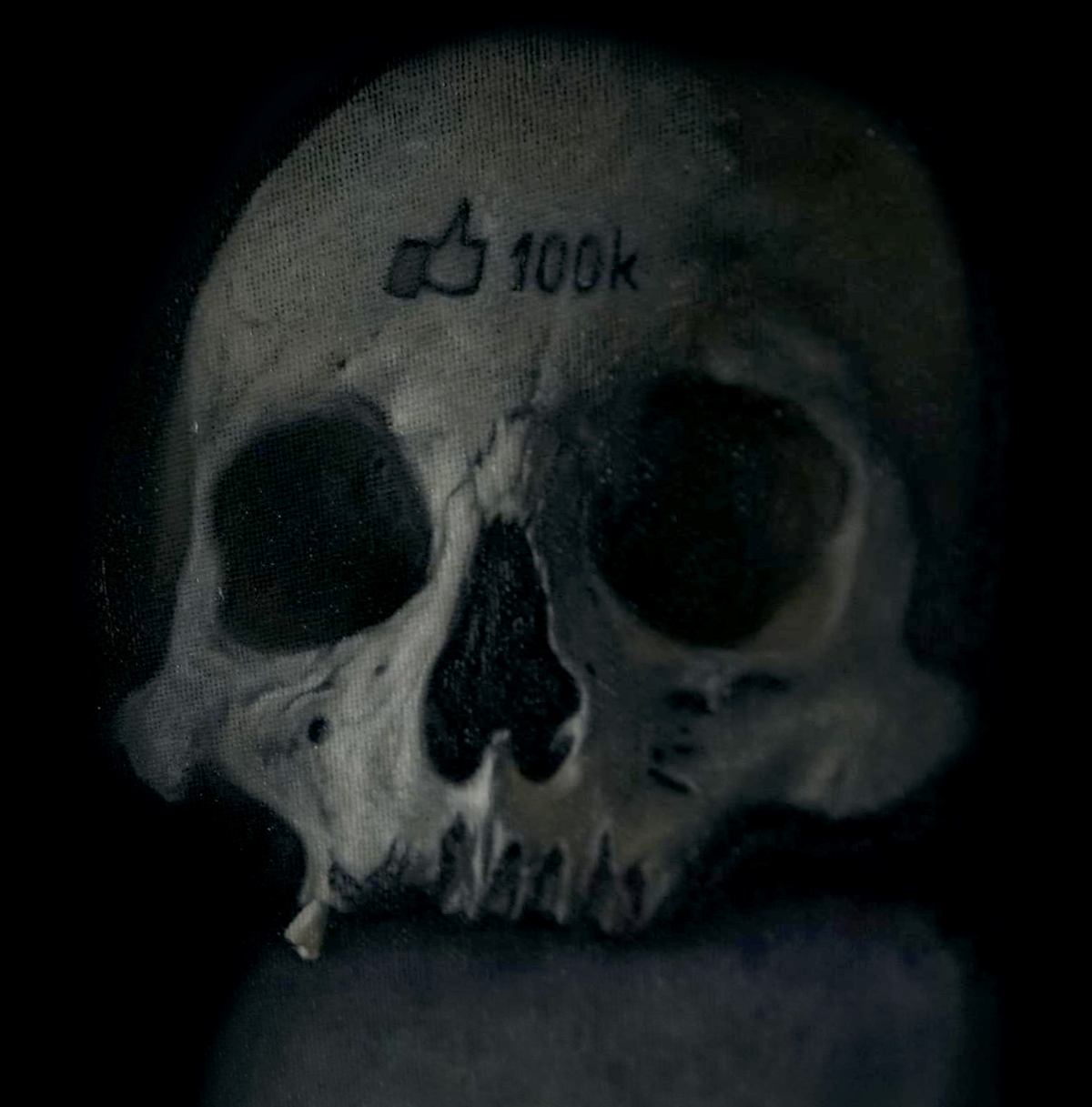

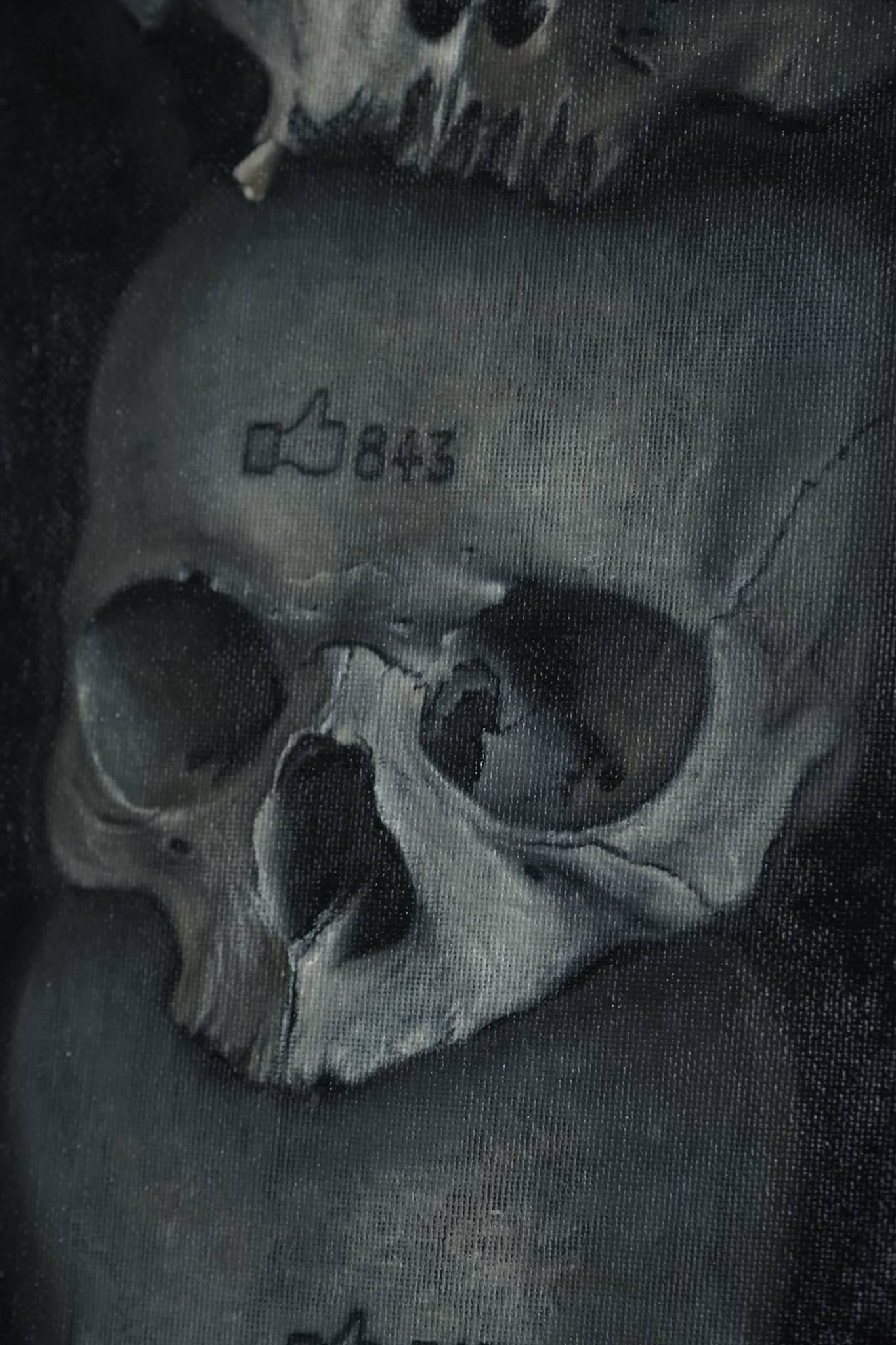

"Ars longa, vita brevis" (Life is short but Art is long), wrote Hippocrates in the 5th century, bemoaning the length of time it takes to acquire skill in the arts. A little later, as a serious young art student myself, I was allowed to borrow a human skull from my college's Biology Department, carefully carrying it back to the studio in a small, battered cardboard box. Once at my desk, I unwrapped the paper tissue reverentially, and began to draw. I suppose you never forget your first one, and I was overpowered by the sense that this was the cradle of somebody's thoughts and dreams I was holding in my hands. My own reaction surprised me, and I don't remember getting much drawing done that afternoon. But I do remember that - horrified by my fellow-students' desire to make it talk - I soon protectively rushed it back to the lab.

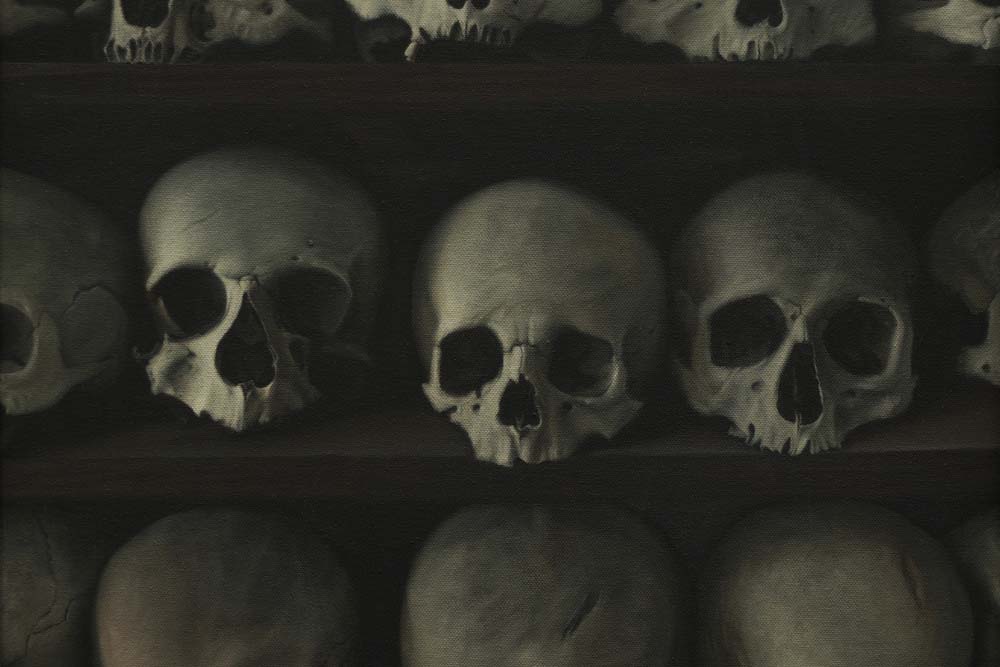

Another Latin phrase, "Memento Mori", means literally Remember Death, or more pertinently, Remember That You Will Die. Not the most pleasant of thoughts, and one which is practically taboo in our culture. However, in ancient Rome, when a triumphant General paraded before the populace, it was one person's official job to whisper, “Respice post te. Hominem te esse memento. Memento mori.” (Look behind. Remember thou art mortal. Remember you must die.) Or the slightly snappier, "Sic transit gloria" (Glory fades), to help keep his feet firmly on the ground. As poet Thomas Gray neatly paraphrased in the mid-18th century: "The paths of glory lead but to the grave". Unlike life, the idea of Memento Mori is a very enduring one.